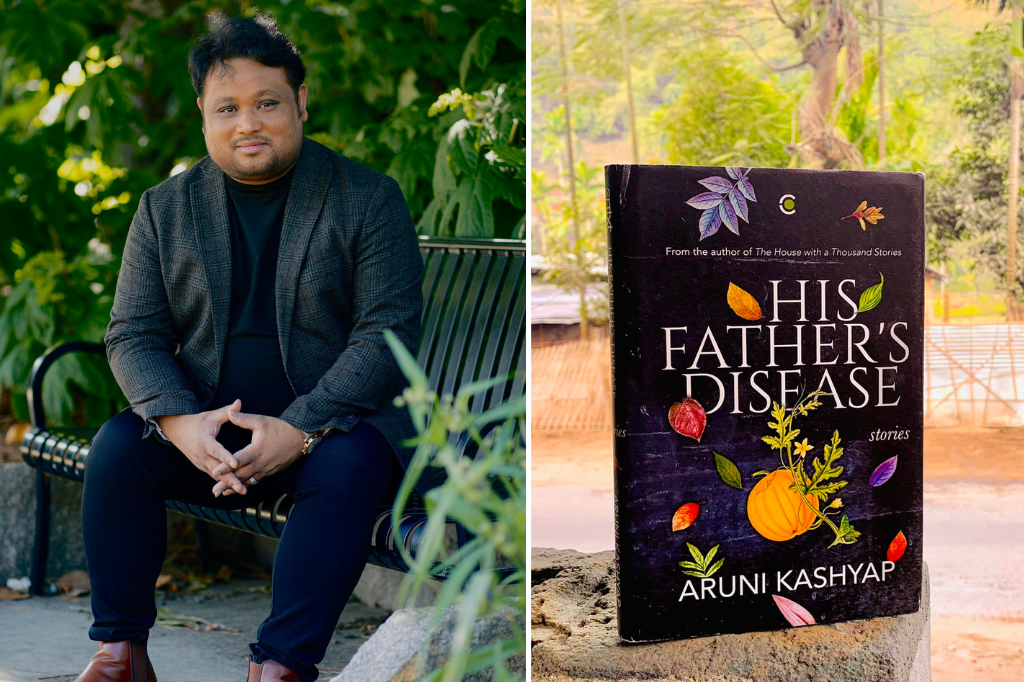

From the lush landscapes of Assam to the academic corridors of the United States, Aruni Kashyap’s literary journey is as expansive as it is rooted. A celebrated Assamese writer, poet, essayist, and translator, Aruni’s work speaks with quiet urgency about the silences that shape our histories – both personal and political.

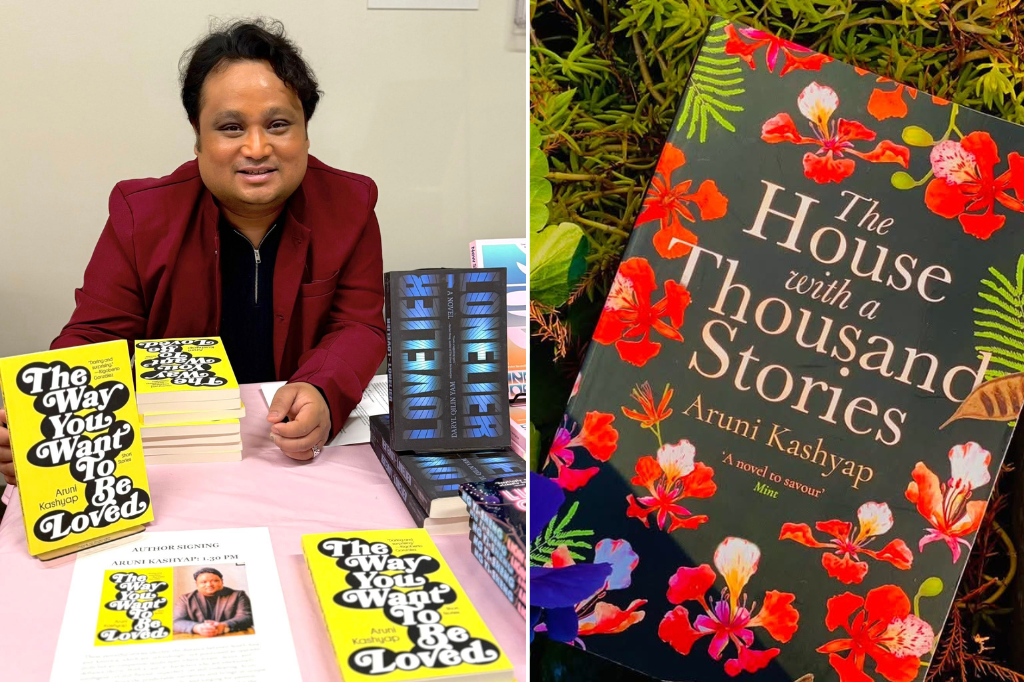

Known for his powerful debut novel The House with a Thousand Stories, and his poignant poetry collection There Is No Good Time for Bad News, Aruni’s voice bridges the vibrant oral traditions of Assam and the contemporary concerns of Anglophone literature. With feet planted in two worlds, he reflects on writing in multiple languages, translating forgotten Assamese gems, and bearing witness through fiction.

Currently a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard and an Associate Professor at the University of Georgia, Aruni continues to challenge and expand the boundaries of Indian English writing. Assam’s insurgency, moments of queer longing, and the dissonance of diaspora are not portrayed to explain or define, but to offer glimpses into lives too often overlooked.

“If readers are moved, challenged, or even unsettled by these stories, then the writing has done what it was meant to do,” says Aruni. For him, writing has always been more than craft – it is an act of remembrance, resistance, and radical empathy.

In this conversation, we talk about the stories behind his stories – what inspires him, challenges him, and keeps him writing. We explore questions of identity, language, belonging, and the responsibilities of a writer in uncertain times.

Your debut novel, The House With a Thousand Stories introduced readers to a richly textured Assam marked by beauty and unrest. How did that book set the tone for your later work?

With my first novel, I wanted to challenge dominant narratives in Indian English literature, which often focus on urban, upper-class and immigrant experiences. The House With a Thousand Stories aimed to spotlight a different India – one negotiating the failures of the state, living amidst systemic violence, yet continuing to find ways to celebrate life.

Growing up in Assam during the insurgency of the 1980s and ’90s meant living under constant threat. My book tried to represent that reality, and in doing so, set the tone for my later work – one that focuses on marginalized experiences and depicts life in an underreported part of our world. I also hope it laid the foundation for the kind of literature I strive to create: literature that centers human rights, that takes the side of silenced communities, and, in many ways, stands on its own as a new kind of writing not often seen in Indian English literature. That was always my goal.

The Way You Want to Be Loved explores the tension between personal desire and societal expectations. How much of this reflects your own experience as an Assamese writer working across cultures?

I wrote those stories because I didn’t see people like me—Assamese, from Northeast India—represented in diasporic literature. While studying creative writing in Minnesota, I read many immigrant narratives but felt disconnected from them. Most were urban, upper-class, and centered around characters who navigated global cities with ease—unlike people from my background.

Even though I grew up in a city, my roots are in rural Assam. My fiction blends this background with Western narrative forms. I’m deeply attached to indigenous storytelling tradition – oral, folk, and testimonial – and I’m interested in what happens when those traditions meet the Anglophone short story.

Many of your characters, especially queer ones, navigate conservative societies in India and abroad. How do you approach portraying resistance and tenderness in such spaces?

As a writer, I look for stories—about characters, their desires, and the obstacles they face. That could mean erotic desire, personal ambition, life goals, or something else entirely. Conflict creates tension, and tension makes for good storytelling.

There isn’t a single “method” to writing queer characters. What’s needed is empathy and imagination. I focus on who they are as people first—their inner lives, their goals. Tayari Jones once said, “Fiction is about people and their problems, not problems and people.” I believe that deeply.

Assam’s history of insurgency recurs across your poetry and fiction. How has growing up amid this conflict shaped your voice as a storyteller?

It shaped me in profound ways. When I moved to Delhi to study English literature at St. Stephen’s College in 2004, I realized my childhood experiences were very different from those of my peers—unless they came from other conflict zones like Kashmir or Maoist-affected regions. But those encounters were extremely limited.

Many didn’t believe the stories I shared. Some thought I was exaggerating or maligning my home state. That pushed me to write—so others could understand what it meant to grow up in Assam during that time, where violence was normalized. That history continues to shape my writing, especially in how it affected everyday people.

Folklore and magical realism—like in Skylark Girl—often surface in your writing. How do you blend oral tradition with modern narrative, especially when writing in English?

Writers like LeAnne Howe, Louise Erdrich, Zitkala-Ša, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Ben Okri have done this beautifully, and they’ve inspired me. I don’t see folklore or magic realism as separate from the literary tradition—they’re integral to it.

My family comes from Mayong, often mischaracterized as a center of ‘black magic.’ In reality, it’s a hub of healing practices and indigenous knowledge. Figures like Tejimola run through Assamese society and imagination. I’ve often been advised to write more urban, mainstream stories for greater commercial success, but I’ve always resisted that. I want to center folklore, magic, and spirit worlds and not treat them as fringe elements.

As a multilingual writer, how do you negotiate the challenges of writing English that carries the rhythm and sensibility of Assamese, while reaching a global audience?

I grew up reading in both languages, so it came naturally to me to write in both. But there’s a joy in stretching the possibilities of the English language. It’s flexible, porous – absorbing words, rhythms, and influences from many cultures. That’s what makes it exciting for me.

I try to carry the lilt of Assamese into English, crafting a kind of English that echoes the orality and cadence of Assamese. I enjoy blending Assamese metaphors, idioms, and worldviews into English prose. If you tell a good story, people will read it – regardless of language. But when language itself becomes part of the storytelling, it deepens the experience.

Now based in Georgia and part of US academia, how do the themes of displacement and outsiderhood in your work reflect your lived experience across Assam, Delhi, and the US?

It has helped me bring to the center stage the underrepresented and often overlooked experiences of a community within Indian English writing. There are very few voices from Assam in this space – just a handful of us. By contributing my voice, I believe I’ve helped expand the scope of Indian English literature while adding complexity to diasporic narratives shaped by brilliant writers like Akhil Sharma, Rakesh Satyal, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Bharati Mukherjee.

While the diasporic experience is deeply important to me, I wanted to present a different kind of diaspora – a diasporic sensibility rooted in the Northeast, specifically Assam. We are a small state in a very large world, and it felt essential for me to tell the stories that shaped me. Of course, writing from this position has its consequences, but I hope my work contributes meaningfully to the broader body of Asian-Indian and Indian-American writing.

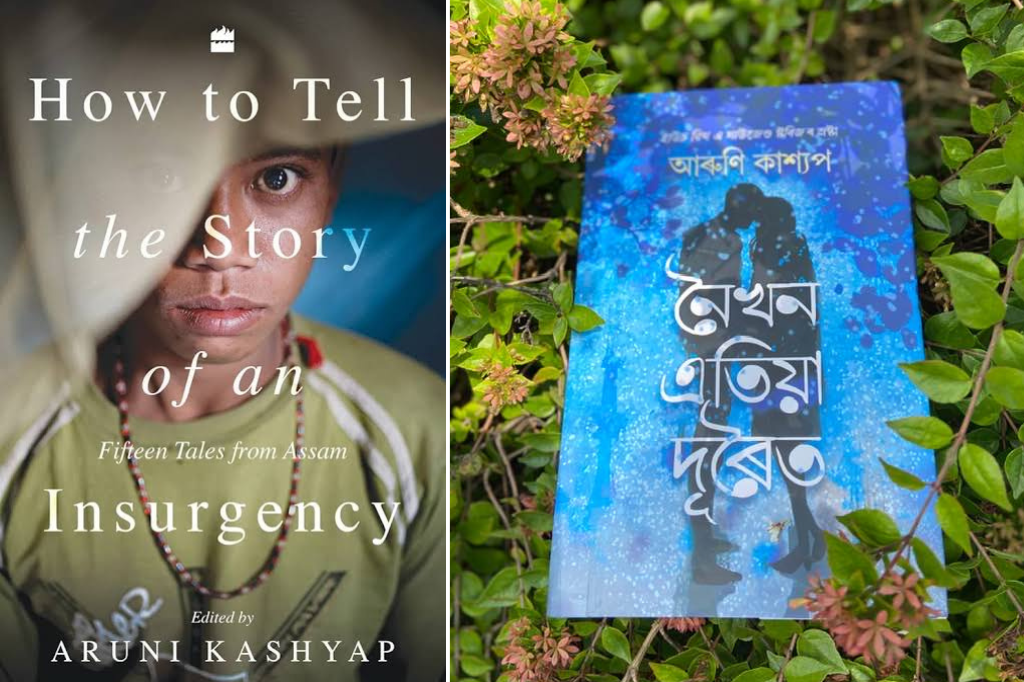

You’ve translated four Assamese novels and edited How to Tell the Story of an Insurgency. How do you see your role in amplifying voices from Northeast India in national and international literary spaces?

Honestly, it’s been an unintended role…but one I feel proud of. I don’t want to be the only one writing about rural, insurgency-era Assam. Earlier Assamese Anglophone writing largely reflected elite, urban perspectives – what some call ‘Gauhati Club literature.’ But Assam is predominantly rural. How to Tell the Story of an Insurgency was my effort to bring forward voices from outside the privileged centers. It’s crucial to document and translate stories from communities that have been historically silenced or ignored.

You’ve spoken about the limitations of the mainstream English literary canon. What changes do you hope to see in publishing to better reflect Northeast India, queer identities, and other marginalized voices?

We need more mentorship and more intellectually curious editors who are willing to look beyond their immediate social circles, the privileged ones. Publishing needs to be more adventurous and open to voices from outside the mainstream. That’s how we build a truly diverse literary ecosystem.

Finally, beyond the themes we’ve discussed – political violence, displacement, queer desire – what stories or experiments are drawing your creative attention now?

I don’t think in terms of themes – I think in terms of stories. But the themes you mentioned are certainly important to academic Aruni and citizen Aruni, and they naturally seep into my fiction. I’m always drawn to short stories that are full of suspense, deeply rooted, and have a strong sense of place—those are the things that attract me as a writer.

Because of that, my personal and intellectual preoccupations often find their way into my stories. But it’s never a deliberate plan to write about a specific theme or issue. Writing fiction that way – starting with an agenda – would be a terrible approach. It would lead to stories even I wouldn’t want to read.